Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Download issue 31 now

PDF file, approx. 1.3MB

The architecture of redemption:

The death and resurrection of Christ in architectural expression

The Christian story of the world’s redemption comes to a climax in the death and resurrection of Jesus. For almost as long as the Christian tradition itself has been underway, that story has been celebrated, enacted, and proclaimed through the built form of architecture.

The cross, by which Jesus was put to death, has easily been adapted to architectural use, but the resurrection has typically required a more abstract and symbolic representation.

A striking feature of the Christian architectural tradition, however, has been the consistency with which death and resurrection are given together. Neither the cross alone, nor resurrection alone, completes the story of redemption. The way to life—to fullness of life—passes through the cross. We cannot have it otherwise.

For the most part, the architecture of Christian faith has maintained this view. Cross and resurrection belong together in the story of God’s dealings with the world.

The architecture of baptism

That the way to new life passes through death is represented above all in the Christian sacrament of baptism, and it was in the architecture for baptism that death and resurrection first received architectural expression.

The cross, as I have mentioned, was an obvious symbol of death, but not the only one. Cruciform baptismal fonts were occasionally found, but more often in the early centuries of the church’s life they were rectangular or square in shape, thus representing a tomb.

The circle, the hexagon and the octagon were also commonly used, the circle representing a womb from which new life comes, the hexagon the sixth day of the week, the day on which Christ died, and the octagon the eighth day, or the first of a new week, the day of new beginnings.

These forms were often given together: the font itself might be cruciform, square or hexagonal, thus representing death, and the surrounding structure of the font, or of the baptistery in which the font was housed, would be hexagonal or circular, thus representing the new life of Christ.

This combination of imagery survives in a contemporary font by William Schickel. Here a cruciform stand, representing death, supports a circular font representing new life.

The architecture of contemplation

What is represented on a small scale in the baptismal font and baptistery receives monumental expression in the architecture of gothic cathedrals. Here too, the proclamation of death and resurrection typically occurs together.

The most common floor plan of the medieval gothic cathedral is cruciform, formed by nave and choir with two transepts representing the arms of the cross.

To be in the church is therefore to be a pilgrim on the way of the cross. That pilgrimage way is represented in the long central aisle and commonly again in the fourteen stations of the cross set out around the perimeter aisles. Contemplating the death of Christ through the stations of the cross in medieval cathedrals and in contemporary churches is a prayerful exercise.

To be a disciple of the Christ here worshipped is to walk with him on the road to Calvary. It is to accept, as Dietrich Bonhoeffer once put it, that ‘when Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.’ Nowhere in the building, and nowhere in the Church, is there any place to walk other than in this cruciform way.

But what of resurrection? There are two great axes in gothic church architecture around which the whole building is conceived. The first is the longitudinal axis, the axis of cruciform pilgrimage, and the other is the vertical.

The pilgrim in the way of the cross does not walk with eyes downcast, for Christ is risen and is now ascended. The pilgrim in the gothic cathedral lifts her eyes to behold the soaring vaults above, flooded with light and testifying to the glory of God. This architecture gives powerful expression to the irreducible connection between the death and the resurrection of Christ.

On earth and in heaven

Sometimes in religious architecture the cross has been placed high in the vaults or domes of the building—in the heavens above, as it were.

This is a dangerous strategy theologically, because it risks removing the cross from the earthly realm. It risks subverting the Christian conviction that Christ died as one of us and in our place, both in our stead, and in the midst of human suffering and sin.

The cross in the heavens serves a dual purpose, however. It reminds us, first, that the risen and ascended Christ still carries the wounds of crucifixion. And second, theologians of the fourth and fifth centuries commonly suggested that a cross in the sky would be the first sign that the second coming of Christ was imminent, and that the day of judgement was at hand.

Although rather poorly executed in some respects, we see in St Columba’s Church (Sutton Coldfield, England) a modern attempt to depict the cross in the heavenly realm, complete with the angelic host blowing the trumpets of victory and resurrection. This cross is also connected to earth, however, thus avoiding the risk of removing the cross from the earthly realm and indicating that heaven and earth are brought together by means of Christ’s death and resurrection.

A more successful expression of this same theme is found in Erik Gunnar Asplund’s Woodland Crematorium (Stockholm, Sweden). A great granite cross is seen on the horizon as visitors walk toward the crematorium. Linking earth and sky, it is a symbol of the resurrection hope. As visitors make their way up the path they are led to the foot of the cross, and are invited to find solace and hope there in the face of death.

The architecture of suffering

The depiction of Christ’s death in the art and architecture of the first Christian millennium focussed almost entirely upon Christ’s victory over death rather than upon his suffering.

It was not until the late tenth century that there appeared (in Cologne cathedral) a crucifix on which Christ is shown exhausted by physical pain and suffering, chest strained, stomach bulging and head slumped forward. This cross, carved for Archbishop Gero, is the earliest known instance of the subsequent preoccupation with Christ’s agony.

In the twentieth century the cross as emblem of Christ’s suffering has probably been the predominant image, supported by currents in twentieth century theology that have emphasised Christ’s suffering with the poor and the oppressed and with those who are victims of human brutality.

The depiction of the agony of Christ’s death may be traced extensively through the visual arts of the twentieth century, but in the spatial arts of architecture and sculpture too, Christ’s suffering has come to the fore.

The great passion facade of Antonio Gaudi’s Temple of La Sagrada Familia (Barcelona) tells the story of Christ’s suffering and death. Note in particular the materials used. The harsh steel girders of the cross—modern materials—contrast with the soft stone of Christ’s body, emphasising the brutality of crucifixion, a brutality not confined to the Roman empire but equally evident in the modern world.

Little progress has so far been made on the construction of the glory facade of the Temple La Sagrada Familia that will in due course complement the nativity and passion facades and give expression to the resurrection, but Gaudi, meanwhile, has followed the medieval convention of cruciform plan and soaring vaults and towers, the latter of which are adorned with the words of the Sanctus, which culminate in the angelical hymn, ‘Hosanna in Excelsis’.

The cross is present in the floor plan of the building. That once the crowd called out for crucifixion is not denied; but humanity’s best and last word, in company with the angels and the whole heavenly host, is a word of praise to the God who raised Jesus from the dead and who in the end, as in the beginning, gives life.

The architecture of humility

Alongside the depiction of Christ’s suffering in recent art and architecture, a second theme has been that of Christ’s humility. There is a place for the depiction of Christ as high and lifted up, but equally important is the humility and lowliness with which he comes among us, nowhere more evident than in his death among thieves.

William Schickel has adopted this theme in a number of churches he has designed. The cross or crucifix is small and is set at eye level, thus present to the gathered worshippers rather than removed from them. The death Christ dies is our death; it is for us and in our midst. And we are called to die with him.

For that reason, Schickel’s crosses and crucifixes are accessible, not removed, but present for us. Christ has come among us in the form of a servant and he is available at the altar for those who would come. Soaring ceilings and prominent vertical elements behind the altar are left to speak of resurrection and ascension.

The architecture of death and resurrection

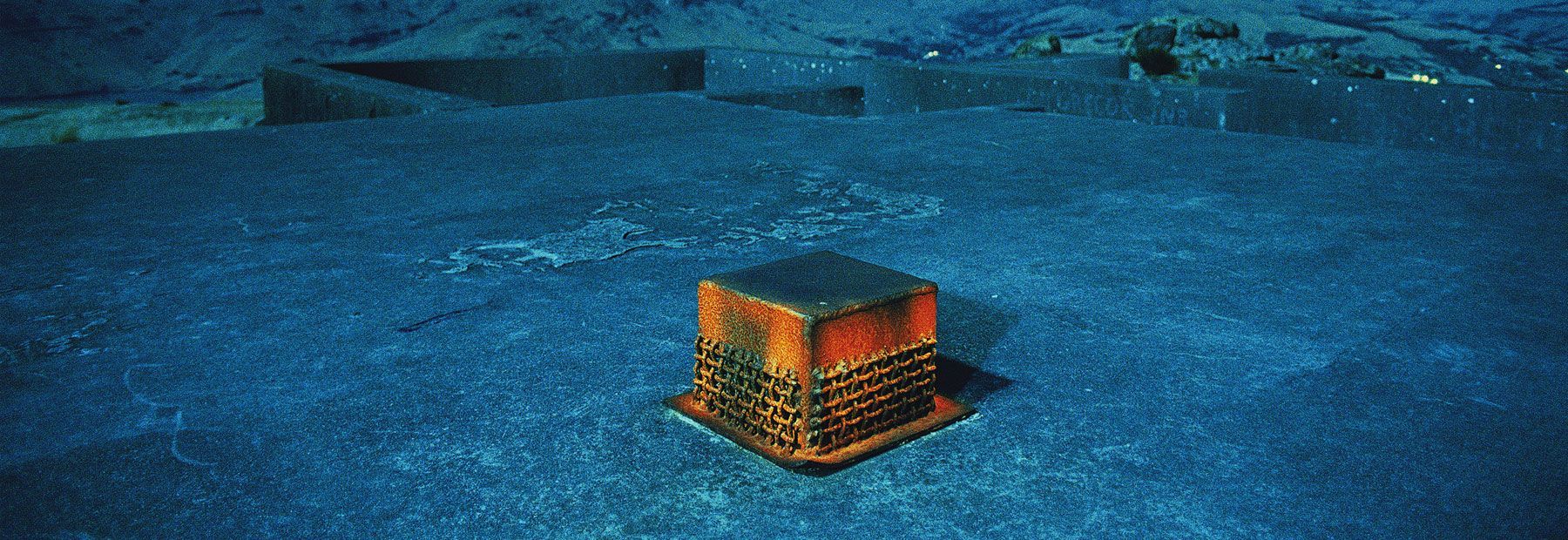

Returning once more to our theme of death and resurrection being given together in the Christian understanding of redemption, Tadao Ando’s Church of the Light in Ibaraki, Osaka, stages a dramatic enactment of the life that comes through death.

Built in 1989, Ando’s church combines the basic Christian symbol of the cross with the imagery of darkness and light.

Access to the church is confined. One does not come accidentally into this space but must seek it out. Careful deliberation and prayerful reverence are appropriate attitudes for those who seek the company of the crucified and risen one.

The church itself is built from preformed concrete slabs. The environment is stark, simple, contemplative. The colour that alone gives relief from the grey walls is the golden colour of the wooden floor and the pews made from recycled scaffold planks, the wood recalling the construction on which another craftsman was executed.

Behind the altar a cross is cut in the concrete, extending vertically from floor to ceiling, and horizontally the full width of the space.

Worshippers may come at dawn into this space and wait—wait for the sun’s light to strike the exterior wall and to make its way, cross-shaped, into the place of worship. The light of God is not at our beck and call. We must wait upon it, and we are reminded that when it does come, it takes the form of the suffering and death of Christ.

The architect himself has commented, ‘Light wakens architecture to life’. The gospel of John begins with the confession that the light of the world has come, and it moves toward the climactic manifestation of God’s glory, made known in the cross and resurrection of Christ. It is the dawning of this light through the cross of Christ that brings life to the world.

Murray Rae (architect and lecturer in Systematic Theology)

- Discuss this article in the chrysalis seed arts community forum

- Return to CS Arts issue 31 - October 2008

- Browse the CS Arts archives

- Other articles available to read online