Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

How the Light Gets In:

The Christian Art of Colin McCahon - Part 3

The Artist

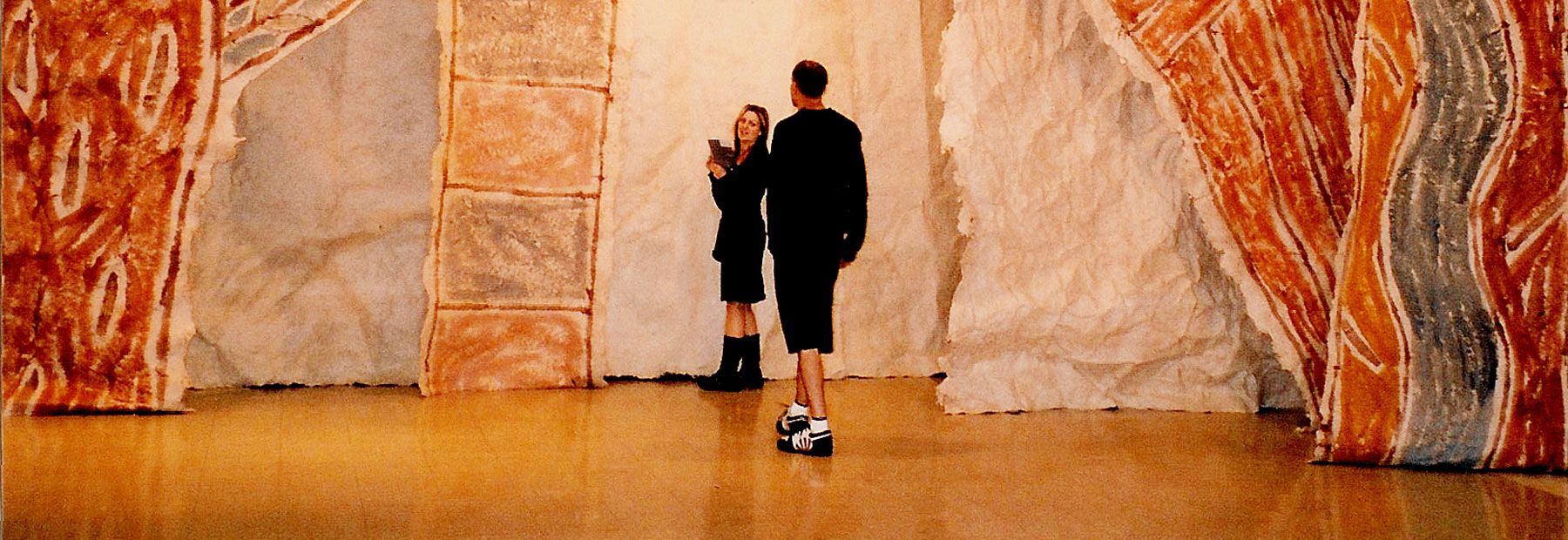

In 2002, Marja Bloem, Senior Curator of the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam brought together for the first time a comprehensive exhibition of McCahon’s paintings from throughout his entire career. Entitled Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith, it was brought to New Zealand with the organisational support of the Auckland Art Gallery, Toi o Tamaki, and made available free to the public of New Zealand by the generosity of two anonymous benefactors. It showed in the Auckland Art Gallery from 29 March until 15 June 2003.

The exhibition brought together 78 works tracing the development of McCahon’s art chronologically from 1946 to the early 1980s. Never before had these works been in one place—not even in the artist’s studio. In a courageous departure from the secular premise of many earlier exhibitions of his works, A Question of Faith recognised the central importance of Christian themes for McCahon’s life and art. It was organised around the artist’s spiritual quest, showing how he explored questions of faith and doubt, meaning and despair. ‘My painting is almost entirely autobiographical’, McCahon once wrote, ‘it tells you where I am at any given time, where I am living and the direction I am pointing in.’6

McCahon’s greatest contribution was to contextualise a Judaeo-Christian vision in New Zealand art. As Marja Bloem says, ‘landscape and religion ... are constant factors in his life and work.’7 For the first time international recognition was given to a leading New Zealand artist for his grappling with the great religious and existential questions of our time. Rudi Fuchs, former Director of the Stedelijk Museum says, ‘McCahon was the artist who gave New Zealand a powerful visual identity. ... That he went further, to explore and communicate through the medium of painting the universal questions and concerns of humanity, is why we, in other parts of the world, must recognise him as a great modern Master.’8 It is a measure of his greatness that he bore witness to religious themes when it was very unfashionable to do so.

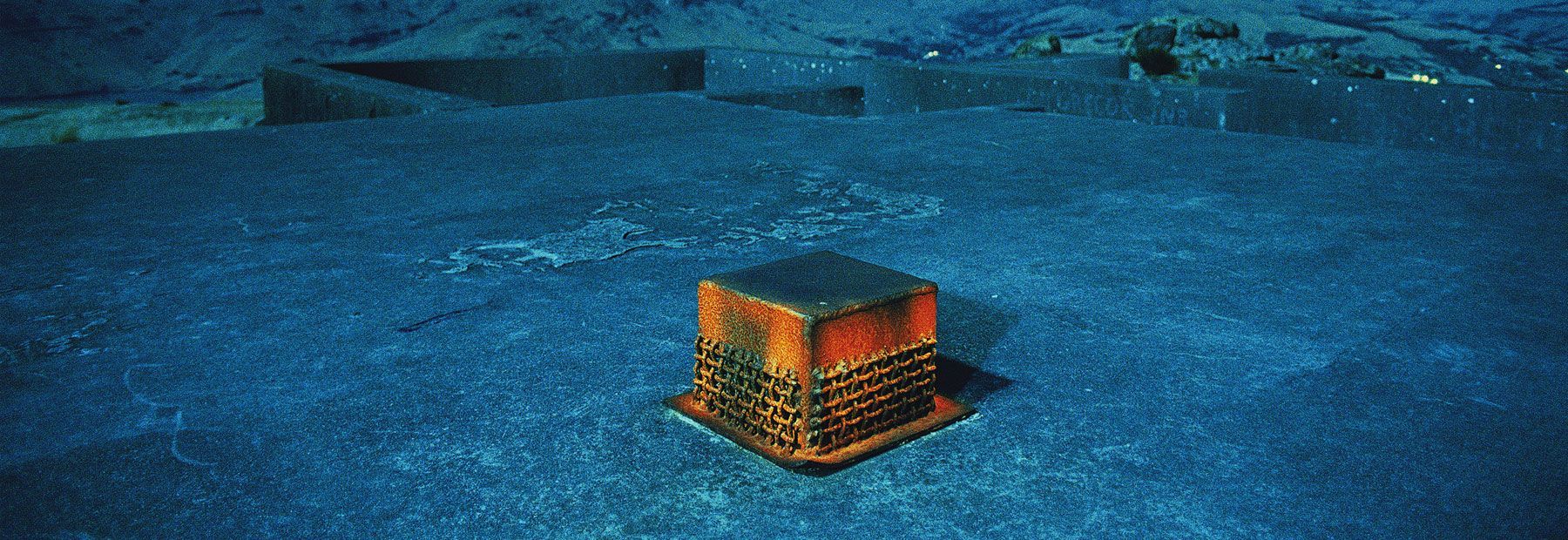

In The Promised Land (1948) McCahon shows his love for the natural beauty of New Zealand, and yet a longing for a perfection that lies beyond it. Dressed in his black workman’s singlet he places himself in the painting, beside the Takaka Hill, with his red workman’s hut to the right. Superimposed on this—a painting within a painting—is a vision of a future paradise represented by the scene beyond the hill: the landscape of Golden Bay, with the hills of Takaka now in the foreground, the view towards Farewell Spit in the background, and the artist (or perhaps an angel) looking down envisioning it. McCahon is affirming more than the goodness of God’s creation. Far ahead, beyond the barren hills and toil of present experience, across the golden strand, he glimpses a promised land of fruitfulness and beauty, the almost forgotten Christian dream of an earthly millennium.

In Beach Walk (1973), a fourteen-panel painting of Muriwai Beach more than twelve metres long, the Christian theme of life as a pilgrimage combines with the Maori tradition of the journey of the spirits of the dead to the place of their departure at Cape Reinga, the northernmost point of Aotearoa/New Zealand. It was moving to see this painting exhibited in a room large enough to stand back and see it whole and at a distance—to recognise the West Auckland coastline in its elemental expanse, its starkness of sand and sky, its changing moods of cloud and current. ‘I do not recommend any of this landscape as a tourist resort,’ said McCahon. ‘It is wild and beautiful; empty and utterly beautiful.’9

McCahon reduced the New Zealand landscape to its characteristic elements and shapes, rather like the drawings in C A Cotton’s famous textbook Geomorphology of New Zealand (1922), given to him as a wedding present in 1942 by fellow-artist Patrick Hayman.10 Whether the folds and escarpments near Oamaru (in North Otago Landscape, 1951), the cliffs of the gannet colony at Muriwai (in the Necessary Protection series of 1972), or the round curve of his favourite hill at Ahipara in Northland (in the left panel of Gate III, in Venus and Re-entry, 1970-71, and in A Painting for Uncle Frank), McCahon’s landscapes, at first glance so generic and stylised, can be recognised as concrete and exact.

Even the use of text in McCahon’s art reflects his observation of the New Zealand landscape, as his son William recalls: ‘The sign painting of roadside stalls is often talked about by commentators as an indication of the genesis of his style of graphics. But this too was a deflection of intent by Colin in response to persistent questioners. In fact, the source of this idea was the religious graffiti once common throughout New Zealand. Taking the form of Bible texts or slogans such as ‘Jesus Saves’, these messages were emblazoned in large letters on walls, overhead bridges, and the natural blackboards of rock faces. These amateur sign painters mostly used white house paint and house-painting brushes to make their words quickly and effectively.’11

Behind McCahon’s lifelong fascination with painted text lay an early formative experience. When he was a child in the mid 1920s, two new shops were built next door to the family home in Highgate, Dunedin. One had its window painted by a signwriter with the words ‘HAIRDRESSER AND TOBACCONIST’. ‘I watched the work being done’, says McCahon, ‘and fell in love with signwriting. The grace of the lettering as it arched across the window in gleaming gold, suspended on its dull red field but leaping free from its own black shadow, pointed to a new and magnificent world of painting. I watched from outside as the artist working inside slowly separated himself from me (and light from dark) to make his new creation.’12

Though he strove to incarnate the Christian message in a recognisably New Zealand context, the religious dimension of McCahon’s paintings was frequently minimised or ignored by academic critics and the general public. To counteract this, McCahon became more direct in his presentation. Increasingly he used words in his paintings because he was discouraged that people were misinterpreting them. ‘Most of my work has been aimed at relating man to man and man to his world, to an acceptance of the very beautiful and terrible mysteries that we are part of. I aim at very direct statement and ask for a simple and direct response, any other way the message gets lost.’13

Article Continued:

- How the Light Gets In: Part 4 - The Believer

- How the Light Gets In: Part 5 - V. The Man

- How the Light Gets In: Foot Notes

- Discuss this article in the chrysalis seed arts community forum

- Return to CS Arts issue 31 - October 2008

- Browse the CS Arts archives

- Other articles available to read online