Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

How the Light Gets In:

The Christian Art of Colin McCahon - Part 5

V. The Man

The Old Testament book of Ecclesiastes is the only book of philosophy in the Bible, the one book in the Bible that speaks to our modern experience of meaninglessness, the only book in the Bible in which God is silent. The biblical ‘preacher’—who is both a philosopher and a prophet—speaks to the existential crisis of our hedonistic consumer culture like no other figure in ancient literature.

In his final text paintings from Ecclesiastes (1980-82) McCahon is clearly contemplating his mortality, pondering ‘the emptiness of all endeavour’. He questions the justice of an existence where ‘Good man and sinner fare alike’ and ‘one and the same fate befalls every one’. He sees ‘the tears of the oppressed’ and that ‘there was no one to Comfort them’. He counts the dead ‘happier than the living’ because ‘all toil and all achievement’ is ‘emptiness and chasing the wind’. He worries that ‘The men of old are not remembered’. His resignation finds expression in the preacher’s fatalism, that ‘the sun rises and the sun goes down; back it returns to its place ... all streams run into the sea.’

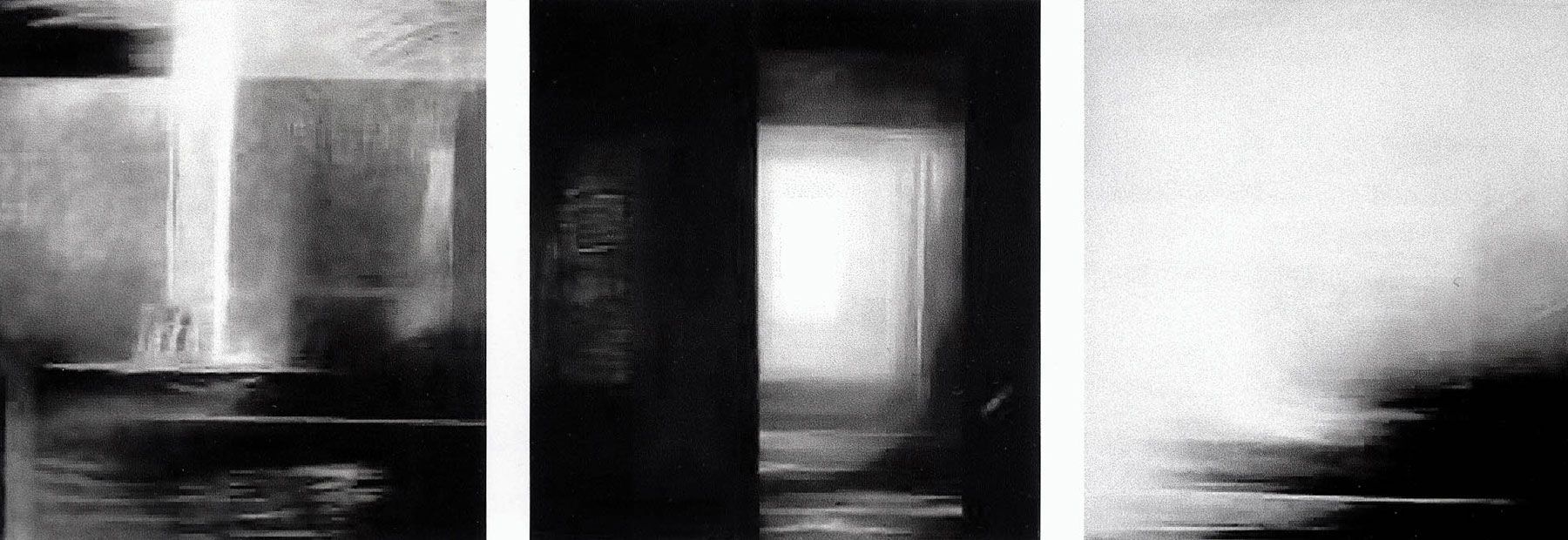

By his sixtieth birthday in 1979, McCahon was a sick man: depressed, drinking heavily, increasingly paranoid about public rejection. All his life he resisted having a television in his house, but in 1983 he turned from his painting to a world portrayed on the flickering screen. In 1984 he fell victim to Korsakov’s syndrome and dementia. ‘Darkness had set in’, says his biographer, ‘blotting out his world.’18

Though the book Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith regards it as ‘a matter of conjecture’ whether in this final period ‘McCahon lost totally any belief in a spiritual Being’,19 the exhibition A Question of Faith was organised on the premise that ‘over the course of time ... McCahon’s attitude evolved from a positive outlook, through a period of doubt, to a feeling of utter despair’, and culminated ultimately in ‘the collapse of his faith’.

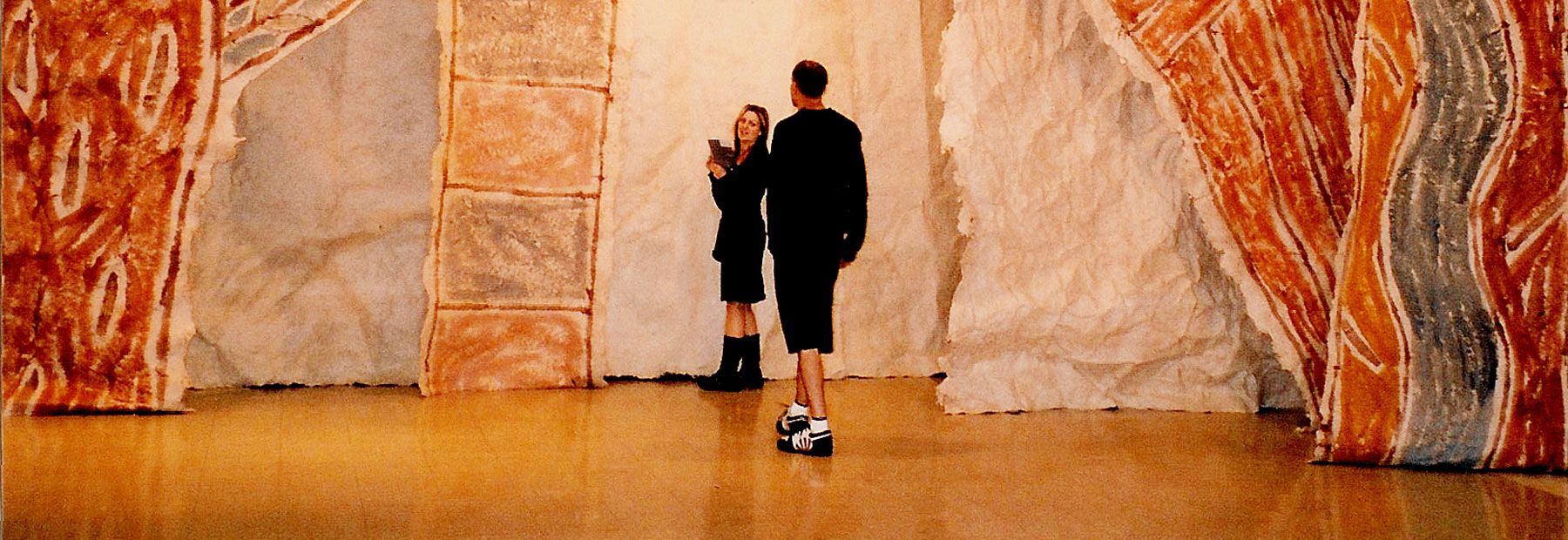

This is too simplistic. The works on Ecclesiastes, though some are dated April and May 1982, were essentially complete by mid-1980, and drew on texts selected in 1979.20 Other works chronologically from this last period—the three orange and black text panels Paul to Hebrews (February 1980), A Painting for Uncle Frank (1980), and even the red and black Storm Warning (1980-81)—are far less bleak. In them McCahon shows a firm grip on faith’s paradoxes, juxtaposing awe of God and awareness of self, divine revelation and human responsibility, God’s eternity and our temporality.

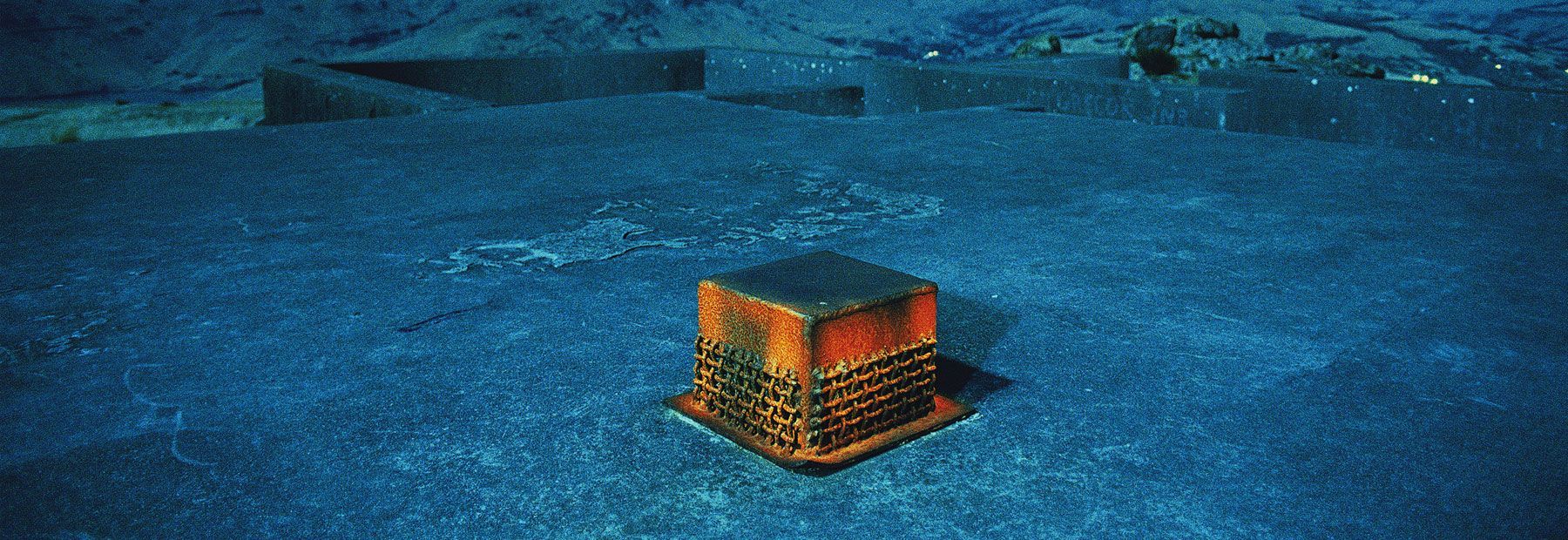

McCahon’s increasing infirmity is evident in the Paul to Hebrews series, with its spelling mistake (‘fourty’ instead of ‘forty’), and the later insertion of an omitted word (‘If even an animal touches the mountain’). ‘Ring the bells that still can ring,’ sings Leonard Cohen. ‘Forget your perfect offering / There is a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in.’21 Despite the artist’s weakness, in contrast to our brief lifespan and human frailty, the third panel shines with a vision of God’s enduring purpose (Hebrews 1:10-12, quoting Psalm 102:25-27):

BY thee, Lord, were earth’s foundations laid of old, and the heavens are the work of thy hands. They shall pass away; but thou endurest: like clothes they shall all grow old; thou shalt fold them up like a cloak; yes, they shall be changed like any garment But thou art the same, and thy years shall have no end

If this be a ‘collapse of faith’, it shows how far secular society, with its shallow optimism, has moved from the realism of the biblical view of life, to which McCahon bore witness while his powers lasted.

Article written by Rob Yule.

Reproduced with permission from Music in the Air, Winter 2006, Songpoetry, 15 Oriana Place, Palmerston North. ISSN 1173-8669.

Article Continued:

Return to:

- How the Light Gets In: Part 1 - The Evangelist

- How the Light Gets In: Part 2 - The Prophet

- How the Light Gets In: Part 3 - The Artist

- How the Light Gets In: Part 4 - The Believer

- How the Light Gets In: Part 5 - V. The Man