How the Light Gets In:

The Christian Art of Colin McCahon - Part 4

The Believer

A common misunderstanding of Christian faith portrays the believer as immune from struggle with doubt. McCahon shows that nothing could be further from the truth. As a Christian artist he struggled with doubt on two fronts: on one, because his faith isolated him in a secular society; on the other, because of the intrinsic ambiguity of faith itself.

The reproach of being a Christian artist was recognised by Alexa Johnston, a close friend of McCahon’s and author of one of the earliest assessments of the religious significance of his work: ‘Colin McCahon’s works have in recent years achieved acceptance and acclaim in the New Zealand and Australian art markets. They are high-status commodities. Yet their religious content is seldom discussed, either critically, or I imagine, around the dinner tables of their owners. ... There is a nagging suspicion that McCahon has somehow let us down by his being a great painter, yet insisting on “bringing religion into it”.’14

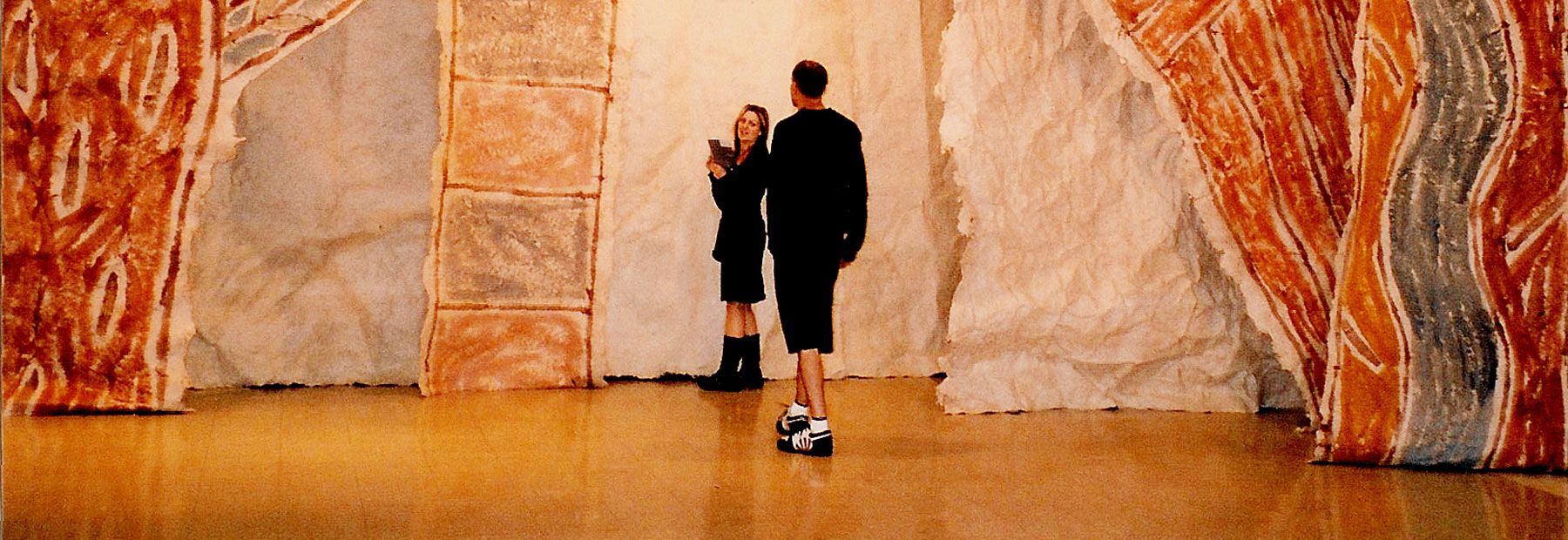

What was notable, therefore, about the 2002-2003 exhibition Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith was that it explicitly acknowledged the central importance of the religious dimension in McCahon’s life and art. It is a mark of McCahon’s greatness that he explored the nature of Christian belief and the challenges it poses in an overwhelmingly secular age. In this he is without parallel among artists in the second half of the twentieth century, and invites comparison with the French Catholic artist, Georges Rouault (1871-1958), in that century’s destructive first half.

McCahon’s personal awareness of isolation can be seen in such works as This day a man is (1970), which includes the words ‘Keep thyself as a pilgrim and a guest upon the earth...’, a quotation from Thomas A’Kempis’s early-fifteenth century devotional classic, The Imitation of Christ (I.23). It demonstrates his feeling of being an alien and a stranger in secular society while also locating him in the great heritage of Christian spirituality.

McCahon’s interest in Maori spirituality was rekindled when his daughter Victoria married into a Maori family. The Lark’s Song (1969) is based on a Maori poem by Matire Kereama. It flows with the liquidity of a lark’s trill, like Vaughan Williams’ ‘The Lark Ascending’. Soaring skyward, the lark seems to symbolise McCahon’s awareness of being a citizen of another world. The painting concludes with an appeal, in English, to the patron saint of birds and animals: ‘Can you hear me St. Francis.’

McCahon felt that secular New Zealanders were not listening to him. He compares himself to St. Francis, who preached instead to the birds! This echoes a characteristic theme in Eastern Orthodox icons of the nativity, which show animals worshipping the incarnate Christ. ‘The ox knows its owner, and the donkey its master’s crib, but Israel does not know, my people do not understand.’ (Isaiah 1:3).

McCahon’s keen awareness of the ambiguity of faith, on the other hand, is first explored in the Elias series of 1959. This series is based on the conflicting comments of the observers of Jesus’ crucifixion as described in the Christian Gospels. McCahon’s interplay of the words ‘Eli-Elias’ (‘My God-Elijah’), ‘ever-never’, reflects the differing viewpoints of the bystanders at Jesus’ crucifixion, and indeed Jesus' own intense faith-struggle, as to whether God could or would save him.

The ambiguity of faith with which McCahon grappled arises from the fact that God hides himself sufficiently to render faith both possible and virtuous—yet that very hiddenness opens up the possibility of doubt. As philosopher J P Moreland points out, ‘God maintains a delicate balance between keeping his existence sufficiently evident so that people will know he’s there and yet hiding his presence enough so that people who want to choose to ignore him can do it. This way, their choice of destiny is really free.’15

In February 1970 McCahon painted A Question of Faith, which recounts the dialogue of Jesus with Martha following the death of her brother Lazarus (John 11). For this and subsequent text paintings McCahon uses the New English Bible translation to address his contemporaries in everyday speech. ‘I got onto reading the New English Bible and re-reading my favourite passages. I rediscovered good old Lazarus ... one of the most beautiful and puzzling stories in the New Testament. ... It hit me, BANG! at where I was: questions and answers, faith so simple and beautiful and doubts still pushing to somewhere else. It really got me down with joy and pain.’16

The question whether Jesus can raise the dead is both hinted at and doubted in Martha’s reproachful words, ‘If you had been here, Sir, my brother would not have died’. These words are repeated from the middle panel of the large eight-by-two-metre Practical Religion: the Resurrection of Lazarus showing Mount Martha, which McCahon finished slightly earlier (1969-70). In defiance of secularism, this painting boldly identifies ‘practical religion’ with our greatest existential need, the raising of the dead!

Practical Religion is contemporaneous with a little-known McCahon painting Young Man, I Say to you Arise (20 September 1969), in the Manawatu Art Gallery, Palmerston North. It records the dramatic incident when Jesus interrupted a funeral procession and restored to life the son of a grieving widow from the village of Nain in Galilee (Luke 7:14-15). The text, red on a caramel background, reads:

Jesus said, ‘young man, I say to you Arise’ and he who was dead sat up and began to speak

Its shape contrasts strikingly with that of The Dead Christ, the gruesome painting by Hans Holbein the Younger (1521)—which so affected the Russian writer Dostoevsky when he viewed it in Basel in 1867, becoming the foil for his great representation of faith and doubt in his later novels. Where the horizontal form of Holbein’s painting suggests the shape of a casket and the inexorable power of death, the vertical form of McCahon’s painting emphasises Christ’s power over death. The Greek word for resurrection, anastasis, means ‘to stand upright’. In McCahon’s painting you can see the young man sit up—the gap between the stanzas representing the hinge between the torso and the legs.

Unremarked by both art critics and theologians, Practical Religion and Young Man, I Say to you Arise were painted during the years when the nature and reality of the resurrection was being publicly debated throughout New Zealand. They are McCahon’s contribution to the debate, contemporaneous with the affirmation of Jesus’ resurrection by the Presbyterian Church and by two leading New Zealand theologians.17

Article Continued:

- Discuss this article in the chrysalis seed arts community forum

- Return to CS Arts issue 31 - October 2008

- Browse the CS Arts archives

- Other articles available to read online