Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

A full but unfinished life

An interview with April Stevens

Life is what happens, in spite of our plans. Decisions challenge and confront, often having dramatic, life-altering consequences. Who do we look to for our personal values? How do we respond to the world issues surrounding us all—issues such as human rights and the environment? April Stevens has sought God’s standpoint and strength throughout her life. In considering what sort of artist to be, April let go of her own desires, allowing God to refine her character in using her art to serve others. Her belief in a stewardship approach to land development and management has consistently informed and been subject matter for her work. Her personal relationships, her teaching and her own art career have all been aspects for contemplation, examining the impact of the decisions humans make.

Deeply-rooted values

April’s clear sense of self and purpose developed from a young age. A commitment to Christianity at the age of thirteen, a strong sense of family and an inborn appreciation of responsible land use all contributed. April grew up near Fairlie, in a large family with a strong farming lineage. She questioned the boundaries concerning genetic engineering even in high school, asking herself ‘What is the thinking behind this? What are the possibilities from here?’

She believes this inquiring nature came from her father’s appreciation of the land and his scientific approach to farming. He and his family believed in a stewardship approach to land development and management. This was combined with her mother’s penchant to recycle, reuse and conserve. ‘Both had a love for the land. More than an emotional attachment, it is a relationship of understanding with it—linked with science and history, an understanding of past and present, and projecting into the future.’

Challenging accepted beliefs

A love and talent for art showed itself in high school, and April began her study of fine arts at Ilam in the mid 1970s. The experience was not what she had expected; she found the environment extremely biased towards male students, and felt the resultant pressure of these attitudes. ‘I can only remember receiving one direct comment regarding my art, from a tutor during a life drawing class. They tended to spend time with the guys. Overt comments were made that we as women were expected to become housewives, mothers or teachers.’

April knew she did not agree with the traditional role and social expectations being put upon her—perhaps due to the influence of growing up with five brothers. Her determination to choose her own path was strengthened by looking to a wider world context and searching her heart. She resisted the strong shift towards abstraction occurring in the school (following contemporary trends), choosing to align herself with Canterbury’s history of painting and work in landscape.

Seeking God’s perspective

It was important for April to assess God’s perspective on being both an artist and Christian, and how she was to go about it. Questioning her role as an artist, God’s view on art and art’s role in the world—in 1970s New Zealand, when art was generally seen as' ...a peripheral, optional, added extra’—April realized she had to look beyond the local context and also search scripture. ‘He [God] is actively interested in it as a human activity. I discovered it is okay to be an artist, and okay to do it full time.’

Making a commitment against the odds to become a full-time artist, April initially paid her way by working on the family farm. She set dates for exhibitions, with an awareness and acknowledgement of the difficulty. ‘It was important to have those to work towards. I found it very hard to just go into the studio and work, being social by nature and a lateral thinker. So the exhibitions helped with the self-discipline. I was conscious through my family links that I did not want to make work just for the educated elite—I wanted work for a broad audience.’

Testing times

Values observed and absorbed during art school concerning the hierarchy between fine art and design or craft were challenged with April taking design and advertising work as a publicity person for Ferrymead Historic Park. April met and married her husband in 1979. With three children following over the next six years, life changed dramatically. Not long after making the commitment to full-time art, she had to let it go for the needs of her family.

April’s work included designing for mission groups, brought about by her husband’s work and their subsequent travelling. She saw this forced shift to applied art as God dealing with her arrogance; refining her personality and character with practical ways of using her art, serving others and responding to need. ‘In the process I developed my drawing skills, making gifts for friends & illustrations for the church. As the children grew I also illustrated, developed and produced pre-school teaching equipment, based on the Montessori method of teaching.’

An artistic response to conservation

Immersing herself in the parenting and home-schooling of her children led April into formal teaching. She had decided in her teenage years that to teach with authenticity meant a need to also be working as an artist. April redirected her artistic skills back towards traditional fine art; beginning where she had left off, with landforms and strong colour contrasts. Her rural surroundings became her content and inspiration. ‘My work quickly became concerned with the impact of intensive planting and the effects of erosion, monoculture [farming one particular thing, such as sheep, or in forestry, one type of tree], and looking at the fragility of land—as in the planting of pine trees and being aware of what happens to the soil (the high acidity from the needles cuts off the growth of other plants)’

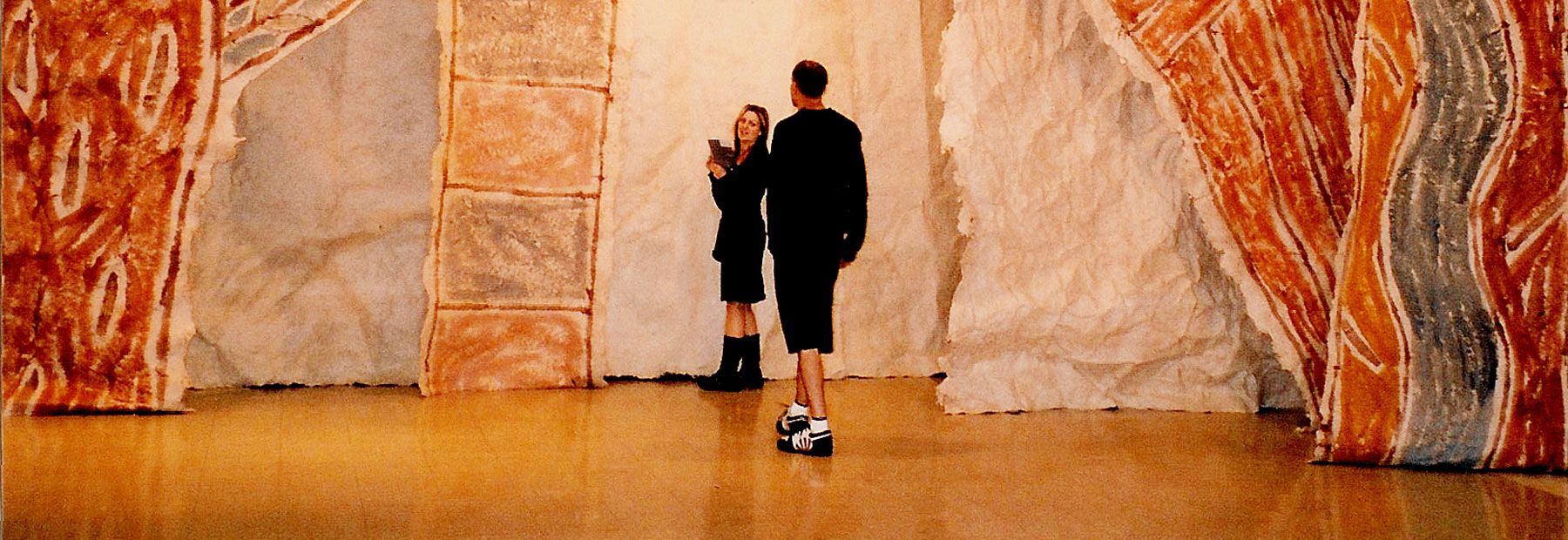

Conservation issues were further addressed later in her career with pieces like No. 4 from the series Can’t See the Wood for... ‘I had been thinking about the trees in the landscape. [I was staying] in Totaranui—there are these European trees ... that create these shaped windows as you look through to the estuary. I started to think of that old adage “can’t see the wood for the trees” so I cut out the trees [literally—out of the painting]. The trees are gone and their shape is created by the negative spaces between the three panels. I returned to emotive vibrant colours and gestural markmaking. My thinking was concerned with the impact humans have on the land and the impact of the decisions we make.’

Acknowledging assumptions

April is also talking about a kind of blindness. Perception, conditioning or culture affects what we see in looking at an issue, a scene or a material object. She hopes to bring awareness of presuppositions held by each of us, and their examination. She asks, ‘Why do we see things? What do I think? What is my response rooted in? I’m an educator and have been for 27 years. Everyone comes from a different background. It is important to be aware of this fact and acknowledge our assumptions. Now as an adult student I am experiencing what I expected to, going to Ilam in the mid 1970s. I am experiencing equality—gender is not an issue.

‘As a teacher it is important to recognise your own humanity, your fallibility—allowing for personal difference, professional difference, variables in beliefs, values, styles of learning and styles of working. Challenging and introducing the learner to new things—that is your responsibility as a teacher; opening a student to new information and experiences, increasing their choices.’

Questions of faith

‘I wanted to have my faith integrated with the content of the work—finding expression within the work. Not “religious” work—I was wanting to raise questions about faith, or get people thinking about what underlies their own preconceptions about the landscape, about life.’ She examined her standing on large ideas.

‘My husband’s mental condition prompted me to think about issues we believe to be true about ourselves, our world and our relationship with the world. I came to understand that what we believe about these things influences what we do and why we do it. What we believe to be true about God, who or what God is. Ourselves—are we a product of chance, or are we design-informed; is there intention in who we are? All key questions to do with us & and the nature of our world: the physical environment, the human and cultural environment.

‘Becoming aware of these things influenced my work. I saw my husband as suffering from depression [he was later diagnosed with Bipolar disorder], I could see why. My perception was that what he believed about these things affected his feelings, which then influenced his actions.’ April and her family experienced 24 shifts of home over ten years. This made life challenging physically with emotional uncertainty resulting from relationships having a lack in continuity. When April and her family did eventually settle, the processing of these life experiences effected and informed her work. ‘I was trying to work these layers into my work. They were dark works, influenced by what I was going through.’

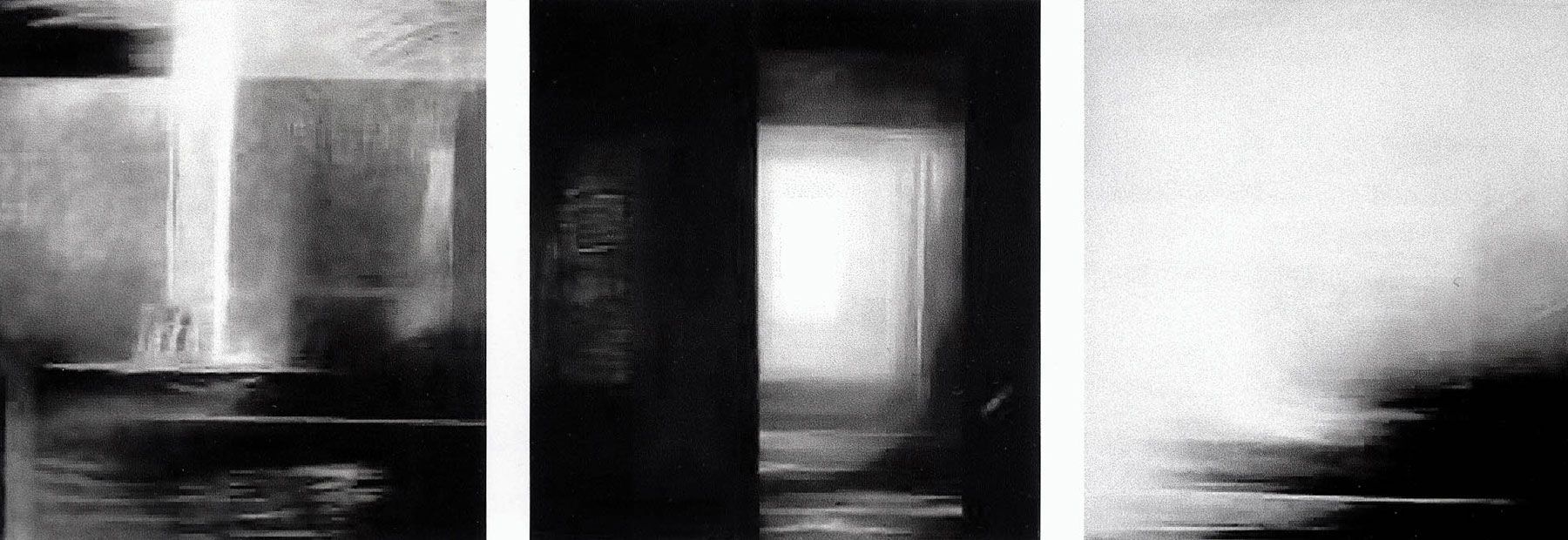

She started carving into the wood, cutting through the gesso in metaphor of her own beliefs and faith. The paint likened the layers people cover themselves or issues in. She continued utilising multiple views, looking at things from a variety of perspectives: ‘Trying to get across the idea that the experience of landscape is never seen from just one place and involves more than one sense. Even looking involves listening and moving. The paintings were ones to interact with, to read then to understand; to look beyond the surface layer of paint.’

Values deepened and strengthened

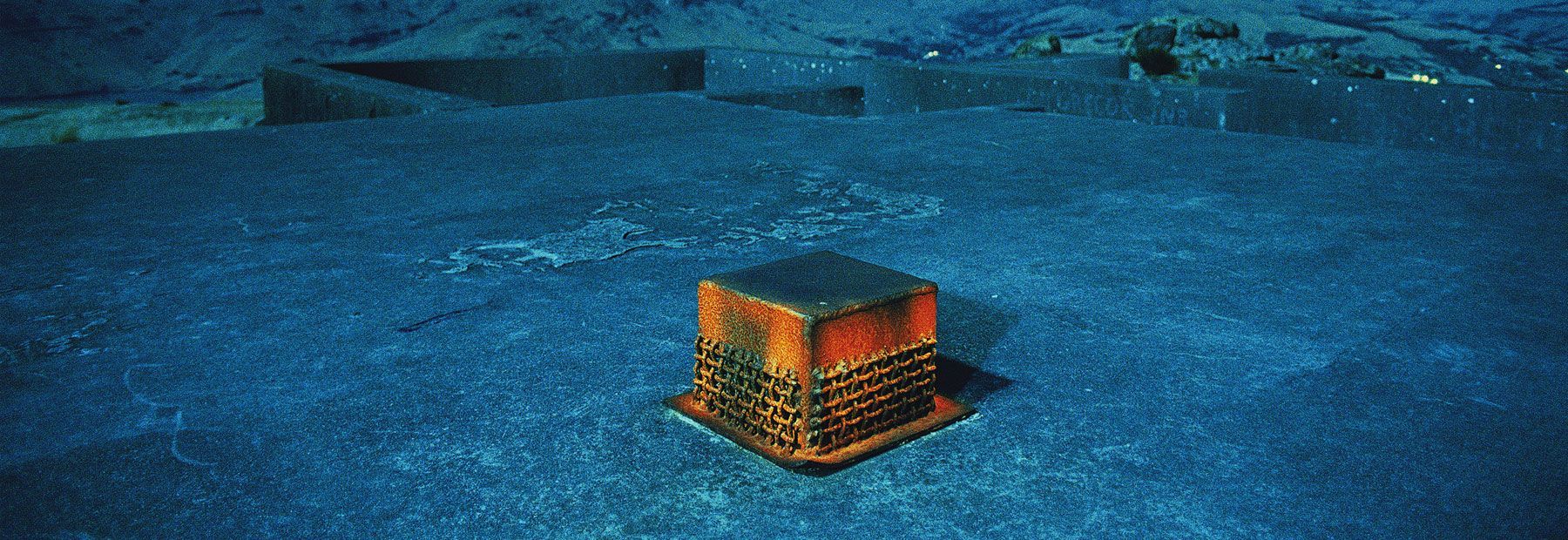

Powerful concepts resulting from deep contemplation continued to inform and inhabit April’s work. A shift from Raumati Beach to Golden Bay in 2001 and part-time teaching allowed time for her art practice. April was asked to contribute to an exhibition for Amnesty International at Pataka Museum of Art and Culture in Porirua. ‘Most of my work had been to do with landscape, and I felt most of my initial drawings were cliched until I got the connection that I could use road signs from the landscape as part of dealing specifically with the declaration of Human Rights.

‘There are 30 articles in the declaration and I produced 21 works, each one for a different article—signs from the landscape as opposed to landscape scenes.’ The work used commonly seen images of signs, adapted to signify individual articles, with the titles adding to the communication. A replica of a Give Way sign was labelled Article 1, and a stop sign labelled Let my People ... article 4. (Article 1 of the declaration states that all human beings are born equal in dignity and rights, and article 4, that no one shall be held in slavery or servitude). This was a successful body of work communicating clearly and boldly. Four of the works showed at Pataka, with the full series showing later in Christchurch and Takaka.

Recent developments

More recently April’s reflection on her life and faith led her to ask her husband for a separation and decide to complete her Masters’ degree. The decisions were not made easily, but she felt they were the right ones for her. Working through the subsequent grief, April gave herself time for the processing. She painted a long scroll, A Full But Unfinished Life, as a tribute to her life and family thus far.

Her work has taken a more abstract turn, looking at maps and mapping, and the reasons behind commissions. ‘Things get commissioned for purposes, and under these purposes is the human motivation: stewardship, development or greed. [It is about] kiatiaki: custodianship.’ Again, April is raising simple but poignant questions: ‘Why do we want land? What do we use it for? What attitudes do we bring to it?’

Where is her work headed? ‘I am discovering that it is a process, a narrowing, a refining ... a letting go of the work enough to let it evolve ... and enjoying the process. I am currently working with found materials and masking tape in creating contemporary installations. This gives me new and interesting challenges. I live a year at a time, with God’s direction.’

Interviewed and written by Janet Joyce