Is God a Postmodernist?

I was born in 1972 at National Women’s Hospital in Auckland. I’m a child of scratch and sniff Sunday School stickers, Abba, polo necks (the first time round), Battle Star Galactica and anti-nuclear protests. I am a child of postmodern times. I am a contemporary artist who works in a postmodern context, as is Franklin artist Vicky-Anne Allen. We are also both Christians.

We both graduated from the Whitecliffe College of Art and Design Master of Fine Art programme in 2006 and work together at Pukekohe High School. During our frequent debates on art and faith, a question we have kept coming back to is this: how can we preserve both the valid claims of postmodernism and biblical truth in our art?

Gallery spaces are the new sacred spaces, where people speak in whispers. But as we whirl through art exhibitions, do we ever take enough time to really contemplate or bear witness? Are we always in a hurry to get the message and move on quickly? In our rush to experience an ‘accelerated sublime’ do we ever make a real connection?

A legacy of suspicion

All of us share similarities with our parents. The same eyes or nose, our features reflect where we come from. It is the same with our postmodern culture, which gets its DNA from modernism.

‘Modernism is characterised by a suspicion of authority and tradition as a source of knowledge, and the conviction that human reason is the engine of progress. This implies that religious faith was a bad guide to understanding the world, and that the unimpeded march of science and technology was a very good thing. The Enlightenment was optimistic: knowledge through reason alone would produce an ideal world which goes on forever forward.’

We now see a reaction to these utopian ideals and the consequences of technological advancement, but not an abandonment of the conclusions.

‘Postmoderism is a parasite within the body of modernity, digesting it with enzymes; it is not a conqueror or a destroyer. No discontinuity is noticeable: which is why some people still feel this a "modern" age, unable to see the thousand simultaneous, invisible paradigm shifts which annulled modernity, fraying at its edges, rather than attacking its core ... What is going on is a reconsideration, a return to reflection, a reappraisal. Can that be so bad?’

Everything is up for revision. But in this chipping away of absolutes, a cynicism and scepticism has infiltrated our imaginations. We are so careful not to get our hopes up over anything, not to put ourselves at risk of believing in something or someone that could get washed away in the next knowledge wave.

On the other hand, I’m a believer in the powerful hope of epic stories. The Bible is the best example. These narratives articulate our hearts; they reveal truths.

Big picture stories

I recently took part in an exhibition called Quartet at the New Zealand Steel Gallery in Franklin with Peter Le Fevre, Gavin Kew and Vicky-Anne Allen. I titled the work I was showing Joyful Myths. This took the form of a series of black and white mono prints and painted signs selected for their quirkiness.

Despite St Augustine rubbing shoulders with Anne of Green Gables, the dialogue was one of hope, judgement, favour and strength: ‘I am She’, ‘Love’s not a competition but I’m winning’, ‘Jesus didn’t come to dig you in but to dig you out’, ‘Join the Pollyanna club and be glad’.

For me making art is about capturing a self-effacing spiritual lightness. Joyful Myths is an invitation to the viewer to enjoy, play and build a variety of possible narratives from images that have become my joyful moments in the visual landscape.

It references both personal and popular culture but the images are taken out of context, suspended within a new body of work. The viewer can flit or swing from image to image. The text can also be seized upon. The viewer attaches the value and the voice to these phrases. Who is telling? And who is told? The statements are by turns authoritative, emotive, playful, deep and directive. They underpin the visual images literally and metaphorically, but they are also intended to subvert and undermine, making the viewer second-guess the surrounding images.

Joyful Myths sits comfortably in the postmodern frame. A work that uses language, text, word play, borrowed images and narratives, letting the author make the meanings. But at the same time the text directly confronts the postmodern distrust of God and the heroic myth.

The signs dialogue human weakness and insecurity: ‘the lack is in me’; but also dialogue hope and faith: ‘I claim the flame’. It acknowledges God and faith are not shattered by being questioned. And that Christians are not diminished by laughing at ourselves or questioning our religious attitudes. This is a space I am happy to operate in.

Mind the gap: beyond word games

As moments of revelation are embedded in narrative they can also be embedded in silence. The works of Vicky-Anne Allen are about the contemplative moment. For Vicky-Anne Allen artworks, life, self, faith and spirituality cannot be defined or wholly articulated. It is in essence a part of the spiritual to defy definition. To put into words what is beyond words becomes the impossible task.

The way she makes work is a way for her body and her being to engage with the materials she uses, light and colour—a visceral response that displaces intellect. Her work focuses on the gap experience of ‘being’ without language.

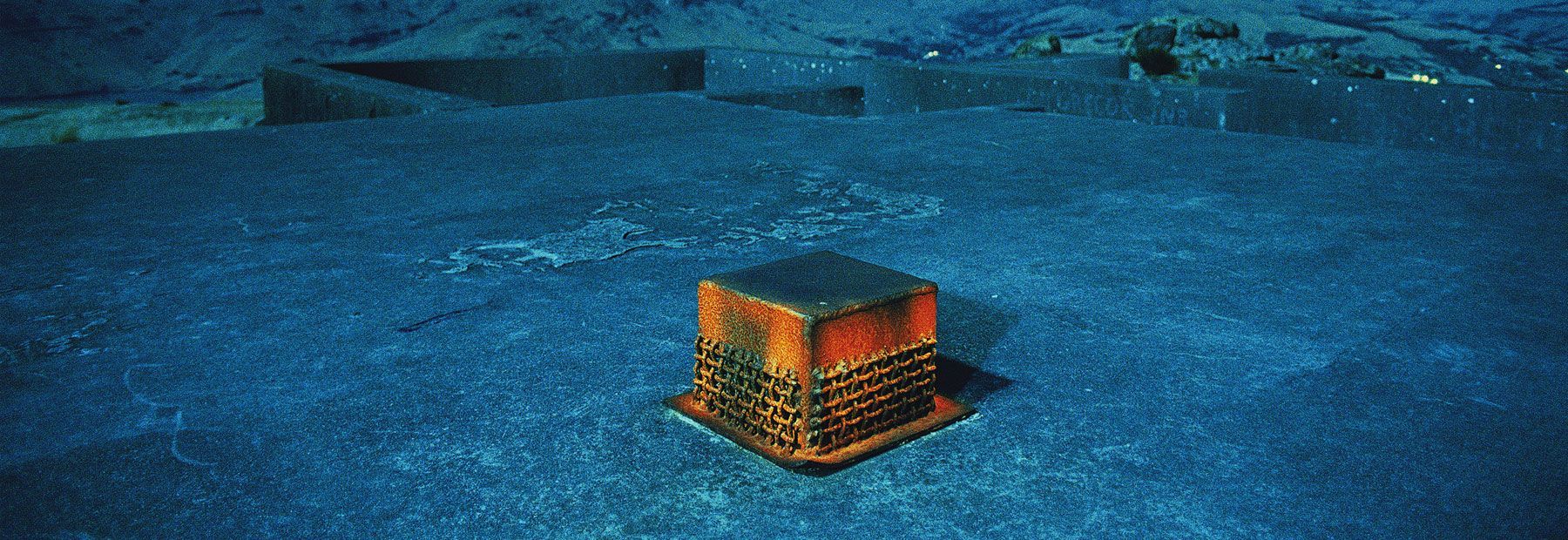

Her life-sized columns of light encased in a skin of paint echo the presence of the body. When grouped in the installation space we experience relationship and interconnectedness with these embodied beings of light—an experience beyond words, senses or intellect that is about being present.

Allen captures heart issues: beauty, joy, love and honour. Using light as a medium has the same quality. It is in us, moves through, between and beyond us.

Allen’s work represents the spiritual journey that she is living. Her longing to connect with beauty, joy and love comes through in her need to make art. This is in reaction to darker elements—the violence, chaos and destruction present in the world around us. She is bearing witness to the light. Light must stand against darkness. Her work reveals this spiritual truth.

Is God a Postmodernist?

In my work lightness, playfulness and frivolity reveal heroic truths and in Allen’s work the lightness is a revelation of spiritual truths. Light is essential to both. Artwork centred on faith can become either message-laden or so light that it floats away.

Allen and I do not wish to make holy images, but we seek to represent fragments of the God we know in our daily lives. As C S Lewis said: ‘My idea of God is not a divine idea. It has to be shattered time after time. He shatters it Himself. He is the great iconoclast.’

In this way perhaps, God is the greatest postmodern thinker. I’m glad just to be along for the ride.

Esther Hansen