How the Light Gets In:

The Christian Art of Colin McCahon - Part 1

The Evangelist

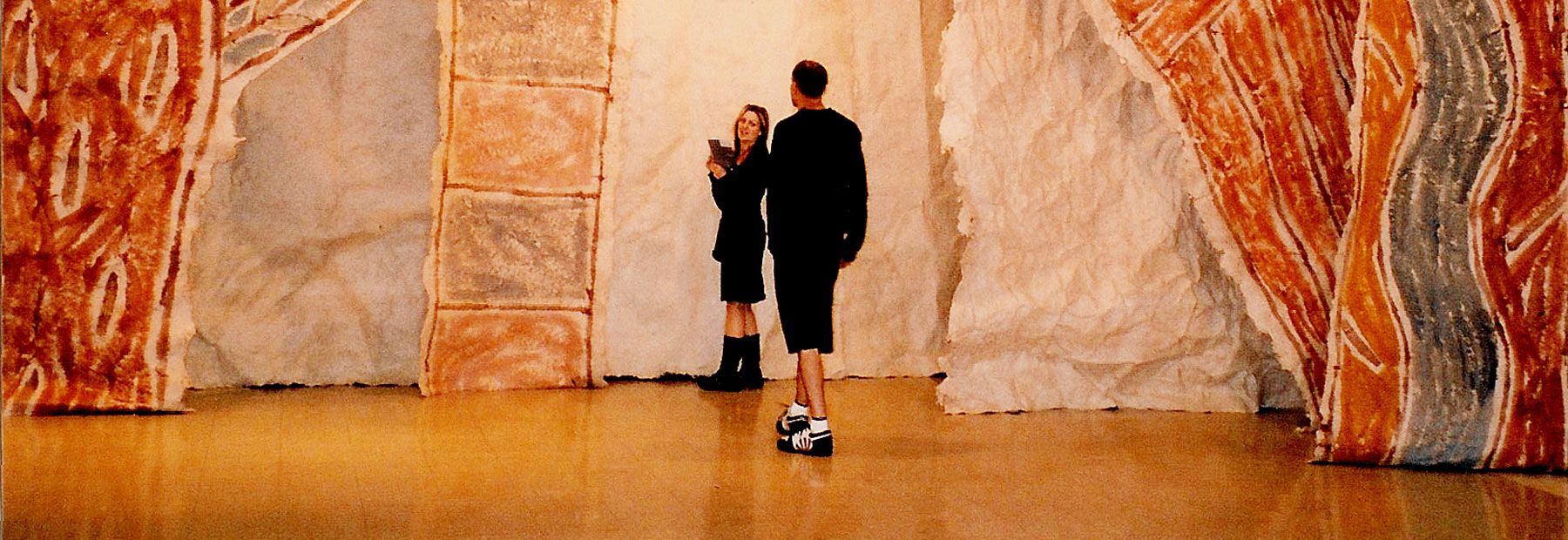

I first encountered a Colin McCahon painting in the mid 1970s when I was Ecumenical Chaplain at Victoria University of Wellington. A gigantic mural appeared on the wall of the entrance foyer of a new lecture block—now known as the Maclaurin Building. It featured an enormous 3 metre-high ‘I AM’ in white and black letters, astride a stylised but recognisably New Zealand landscape, with texts reminiscent of the biblical prophets.

It was a painting to walk past, from left to right. The left panel, showing the lowering darkness of a bush fire or an approaching storm, seemed heavy with foreboding about secular culture, ‘this dark night of Western civilisation’. It reminded me of the words of Fairburn, who a generation earlier had also lamented the burning of the bush and the secularity of New Zealand culture:

Smoke out of Europe, death blown on the wind, and a cloak of darkness for the spirit.1

Toward the right of the painting the landscape brightened. The transition from darkness to light was marked by a series of biblical texts, framed by the giant letters ‘I AM’, God’s numinous personal name, indicating his eternal being, revealed to Moses before the exodus from Egypt (Exodus 3:14). The texts, from the Psalms, included a prayer for self-awareness: ‘teach us to order our days rightly, that we may enter the gate of wisdom’ (Psalm 90:12),2 and an invocation of God’s blessing: ‘God be gracious to us and bless us, God make his face shine upon us that his ways may be known on earth and his saving power among all the nations’ (Psalm 67:1-2).

I remember standing before this vast mural, awed by its impact. It was a profoundly counter-cultural statement—not unlike the ‘turn or burn’ preaching of the Jesus People movement with which it is contemporary—warning that our secular, materialistic society will destroy itself, unless we humble ourselves, seek wisdom, and pursue ‘the Lord, our true goal’. Like an evangelist pressing home the bleakness of the human condition and the majesty and holiness of God to bring about a change of heart, McCahon spread a giant canvas to urge his viewers to leave the broad and popular way that leads to destruction and ‘enter through the narrow gate’ that leads to life (Matthew 7:13-14).

The path of conversion is represented by the very structure of the painting. It moves from the dark, oppressive scene on the left to a landscape of rolling hills and open sky, a world of space and light on the right. Between is the entrance, the gate of wisdom—bounded by the ‘A’ and the ‘M’ of the great ‘I AM’. On the far right McCahon’s text links being ‘born into a pure land’ with the presence of ‘a constant flow of light’. Thus he reminds us that we cannot have fellowship with God unless we walk in the light (1 John 1:5-7), and—by repeating his point twice—that we cannot enter the kingdom of God unless we are born again (John 3:3, 5).

‘When I was young I wanted to be an evangelist,’ McCahon told a friend in the late 1950s, while travelling on a bus to work at the Auckland City Art Gallery.3 Behind such a surprising description of the artist’s calling stands an influential figure. In his youth McCahon worked in the orchards of Motueka, and sometimes visited his artist friend Toss Woollaston. Woollaston’s uncle, Frank Tosswill, was a member of the Oxford Group, a supporter of Moral Rearmament, with its emphasis on evangelical social renewal and four rigorous ideals of absolute honesty, absolute purity, absolute unselfishness and absolute love. ‘Uncle Frank’ used to carry a large rolled-up scroll, with diagrams and texts to illustrate his sermons. When he came to stay he would take down Toss Woollaston’s paintings from the best part of the wall and hang up his scroll instead.

The scroll was more than two metres long, with the sun rising over Tasman Bay, texts in red forming radiating beams, and the words ‘Almighty God’ painted along the top. Toss Woollaston didn’t like it, but the twenty-one-year-old McCahon was fascinated by the poster-style and combination of image and text. One of his last works, in 1980, was A Painting for Uncle Frank. The once-fiery and earth-shaking Mount Taranaki forms a shape reminiscent of the Almighty’s callipers in Blake’s Ancient of Days—and of the radiating sunbeams of Uncle Frank’s scroll. Its text is the great vision of the heavenly Jerusalem in Hebrews 12:22–27. Quoting Hebrews 1:7, McCahon changes the word ‘ministers’ into the singular: ‘He who makes his angels winds, and his minister a fiery flame.’

‘Uncle Frank’ kindled a passion to communicate the Christian message through art that burned in McCahon to the end of his career.

Article Continued:

- How the Light Gets In: Part 2 - The Prophet

- How the Light Gets In: Part 3 - The Artist

- How the Light Gets In: Part 4 - The Believer

- How the Light Gets In: Part 5 - V. The Man

- How the Light Gets In: Foot Notes

- Discuss this article in the chrysalis seed arts community forum

- Return to CS Arts issue 31 - October 2008

- Browse the CS Arts archives

- Other articles available to read online