Identity and Iconography

An interview with Professor Robert Jahnke

Professor Robert Jahnke’s career is an exploration of what it means to be a Maori artist. The influence of Christianity on the heritage of his visual culture led naturally to an artistic questioning of the Church’s role in the colonisation process.

Professor Jahnke now heads Massey University’s School of Maori Studies, and is Coordinator of Maori Art there. He talks to CS Arts about a sculptural practice that reflects the traditions of both Maori and European art.

Constructing identity

‘Identity is a malleable notion that is determined by the context of one’s upbringing. Of course genealogy is an indispensable factor.

'I have suggested that "I am a Maori and it is coincidental that I am an artist". This deliberate inversion of Ralph Hotere’s famous edict that "I am a Maori by birth and upbringing. As far as my work is concerned this is coincidental" is not a criticism of Hotere’s position as an artist, but rather a statement of my commitment to making a contribution to Maori culture beyond my practice as an artist. For me personally this commitment is a cultural obligation.

‘The construction of my Maori identity has been informed and consolidated through my involvement in education, initially within the secondary school system and latterly within the tertiary sector. In the process I have wrestled with the notion of Maori art as a cultural construct and its multifaceted forms of expression, which I have conveniently labelled as customary, trans-customary and non-customary according to the perceptual relationship of the work with "traditional" Maori art.'

Customary and contemporary

‘Contemporary Maori art straddles customary and non-customary practice, with each maintaining adherence and support from a particular sector of society. For many Maori there is a preference for work in which they can see themselves.

'This is particularly evident in customary and trans-customary work, where cultural referents to form and pattern are obvious visual connections. For those artists whose practice is non-customary in a perceptual sense, acceptance by Maori is often tenuous. The problem faced by such practitioners is that the kaupapa Maori (Maori ideology) element often needs to be explained.

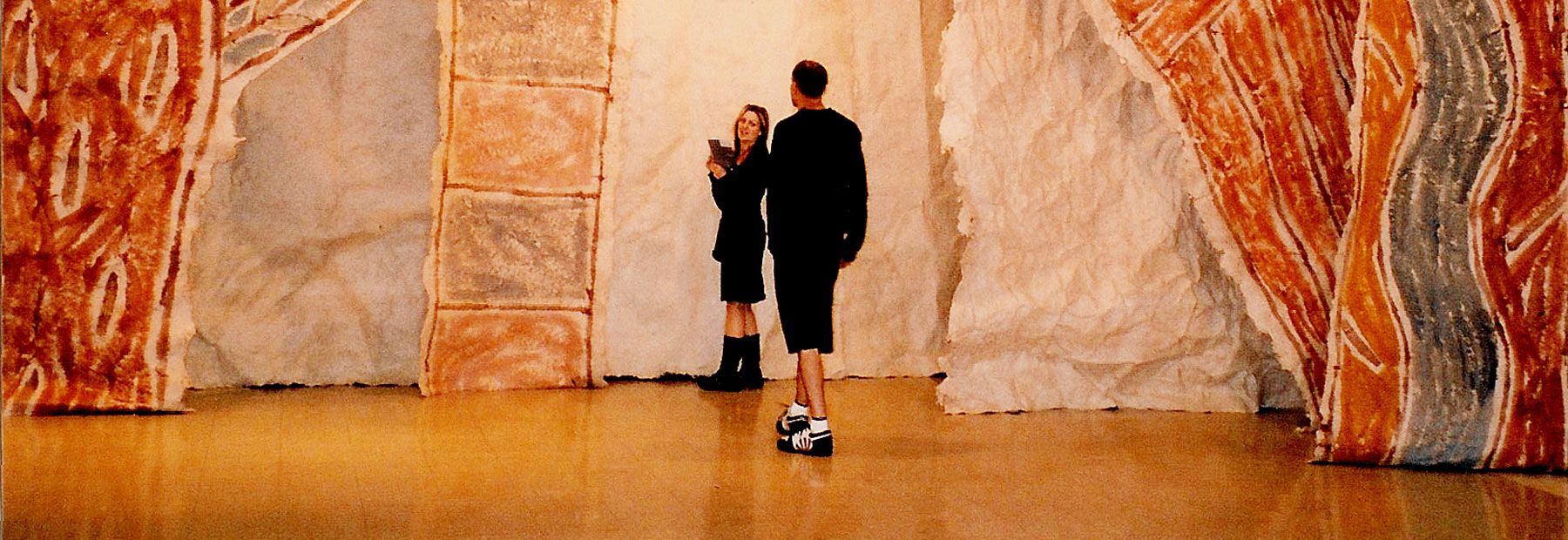

‘My initial transition into sculpture began with a conscious trans-customary phase, in which there was a deliberate cultural reference to the facade of a meeting-house in a series of relief assemblages that owed much to the influence of Matchitt and Hotere.

'During this period my identity as a Maori was a given and I did not engage in articulating my identity. It was also a period when I did not consider myself an artist or a sculptor but rather a fabricator of cultural images. It was not until 1992, when I had moved to Massey University, that reference to customary Maori visual forms disappeared from my visual vocabulary, to be replaced by non-customary forms grounded within a western sculptural tradition.'

A new iconography

‘My personal recourse to Christian iconography is a condition of attending a Catholic boarding school and subsequently entering the academic arena. There the validity of alternative belief systems undermined the Christian dogma that I experienced during my high school education.

‘The critical contribution that the Maori Prophetic movements made towards a re-contextualisation of Christianity was the introduction of a new visual iconography where traditional values infused the rationale for its incorporation.

'For example, Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki encouraged the incorporation of non-customary naturalistic imagery in carving to allow ancestors to be identified. Hence, Maui was often shown with a fish or a canoe relating to his renown as the fisher of islands in Polynesian narrative tradition. Painting moved beyond the convention of kowhaiwhai to include naturalistic imagery of people, plants and even text. In both cases, this was accompanied by the application of a liberal palette of non-customary colours.

‘The enrichment of imagery within Maori contexts is one of the major impacts of Christianity on Maori visual culture historically. However, there are two sides to the Christian sword.

'On one side an accessible iconography evolved as Maori made the transition into a literate society, and on the other customary iconography was denigrated. In my tribal area of Ngati Porou on the East Coast of the North Island, Christianity resulted in emasculated ancestors. My attempt to redress this legacy in my whare nui in 1999 resulted in castigation by kaumatua and a return to the status quo.'

Dual partners

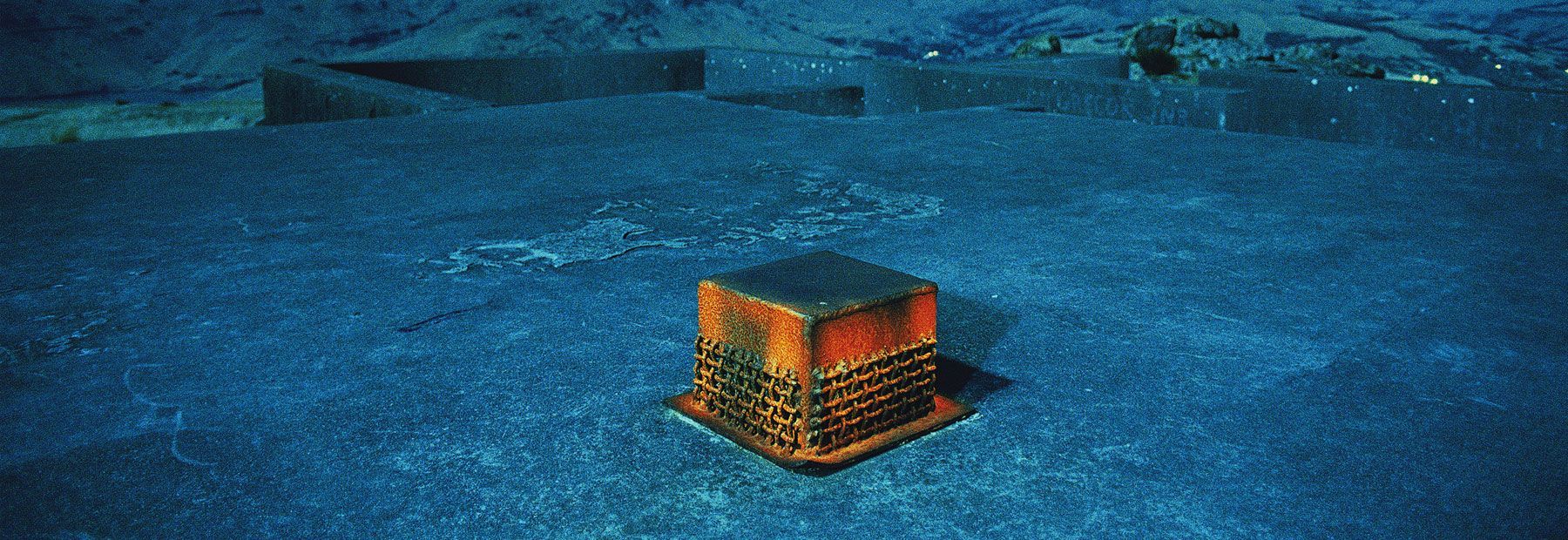

‘Perhaps my most polemic response to the Church’s role in the colonisation process has been Conversion 3.3R, featuring 12 lead-covered axes and Bishops’ mitres referencing the purchase, in 1816, of 40,000 acres in the North Auckland region for 12 axes. This transaction was negotiated by the Church of the Missionary Society on behalf of an absentee buyer in England.

'The inequality of this conversion process is reflected in the title of the work—3.3 recurring, a mathematical quotient that quantifies incommensurable value and alludes to indefinite resolution. On the bishops’ mitres the word "sacred" is inscribed on the base, with "acre" highlighted as an epitaph to lands lost to the Church Missionary Society. The conversion was "utter" theft. Hence the utterance—"ata"—translated as light and shadow, framing arched niches housing the mitres of Christian morality.'

Alpha, Omega and sacrificial lambs

‘In Alpha and Omega, recourse to Psalm 23 as a textual passage appears on glass cases housing freezing work attire and a lamb carcass, as a lament for the closure of works that employed Maori from Whakatu, in Hastings, to Patea.

'In supplementary neon light works, a range of depictions of the parable of the ‘Good Shepherd’ appears as photo-engravings beneath the neon lights, maintaining an elegy to righteous and exemplary behaviour that one expects in a caring society.

‘The lamb carcass is a reference both to dying industry and to Agnus Dei, Lamb of God, the sacrificial lamb. In this respect, Maori become the sacrificial lambs of a restructured industry driven by economic reform.

Alpha and Omega is a reference to the omnipotence of the Christian God as the beginning and the end. A and O together constitute Ao, the Maori world; a world realised through the intervention of the Maori deity Tane Nui a Rangi in the separation of earth and sky.

'Despite the existence of alternative belief systems, Christianity maintains its omnipresence not only in the conversion of many Maori to the Christian faith but also in the Christian construction of Anno Domini—the year of our Lord.'

Professor Jahnke was interviewed by Rob d’Auvergne.